- Home

- Minakshi Chaudhry

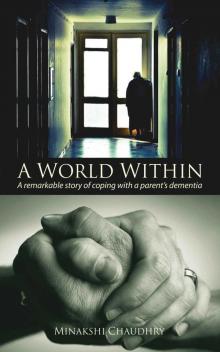

A World Within

A World Within Read online

A WORLD WITHIN

Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd.

Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India

Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA

Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK

Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia

Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa

Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong

Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada

Email: [email protected]

www.hayhouse.co.in

Copyright © 2014 Minakshi Chaudhry

The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by her. They have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a phonographic recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise be copied for public or private use—other than for “fair use” as brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews—without prior written permission of the publisher.

The author of this book does not dispense medical advice or prescribe the use of any technique as a form of treatment for physical, emotional, or medical problems without the advice of a physician, either directly or indirectly. The intent of the author is only to offer information of a general nature to help you in your quest for emotional and spiritual well-being. In the event you use any of the information in this book for yourself—which is your constitutional right—the author and the publisher assume no responsibility for your actions.

ISBN 978-93-81398-76-0

Printed and bound at

Rajkamal Electric Press, Sonipat, Haryana (India)

“To all the parents and their loving children”

CONTENTS

Acknowledgement

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Epilogue

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

To the best dad in the world, you have amazed us all with your dignity and the way you hold your head high even as dementia chips away pieces of your existence. Hats off to you, mom, for your grit, patience and love that you shower while taking care of him every second.

This book would not have been written without the support of many wonderful people. Rakesh, my soulmate, is of course at the top of my list, he is a blessing which I cherish. Thank you for going through the manuscript critically, and providing a lot of suggestions as I grappled with the story. I have no words to express the gratitude for your love and your rock-like support, every time, every day.

Another extraordinary blessing is my teacher and mentor, Prof. Vepa Rao. He was the first to read the manuscript. Your on-going support and encouragement motivates me to take life as it comes.

I am in awe of Ashok Chopra, the CEO and Managing Director at Hay House Publishers, India. He is my teacher too (yes, he taught me about the publishing world when I was a young twenty-year-old, pursuing a course in journalism). Despite his busy jet-setting schedule he always takes out time to be in touch and inspires you with his dynamism. If it was not for him I would not have been able to let people know this remarkable story. My heartfelt gratitude to Ashok Sir, this book came because of you.

Sanjana Roy Choudhury, my publisher, is priceless. She feels like a close friend to me now. Even while she was recuperating after a surgery she made sure the book was on schedule. Thank you, Sanjana.

Tulika Rattan, my editor, made this book as good as possible by her meticulous and painstaking editing. Thank you for being patient with me.

Thank you all at Hay House.

Special thanks to my incredible and tireless friend, Deepshikha, for typing the manuscript at odd hours with a smile on her face.

Works of Thomas DeBaggio, Eleanor Cooney and Lisa Genova made me understand in totality what does a person with dementia and the caregivers go through. I could relate to what they said instantly as I saw my father grapple with this disease. I also acknowledge the support of Alzheimer’s Association, Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centre, National Institute of Aging, Wikipedia and other Web resources. Thanks are due to Shakti Singh Chandel for filling me up on the history of Bilaspur. I credit all of them for making this story complete.

I would also like to thank Prof. Som P. Ranchan who read the manuscript in a couple of hours, boosting my confidence and gave his critical comments and pointers. Sapna and Rahul for your prompt counselling and guidance when I needed it the most.

Thanks to Jaideep Negi, chief librarian, and the entire library staff at the Himachal Pradesh Secretariat for their support and help. Special thanks to Rajinder Aggarwal of Minerva Book House, who flatters my ego by frequently telling me, ‘We are waiting for the next book’.

Many thanks to Mummy and Pita-ji, my parents-in-law, for keeping faith in me and for your ongoing trust.

My siblings Seema (you are an inspiration), Neeraj (my biggest critic, enthusiast and avid commenter), Deepak (a real charmer who knows how to get his way without lifting a finger) – you are the best that any person can have.

My thanks also go out to my extended family – Dalbir jija ji, Anu didi, Pooja, Supriya, Deepika, Chandni, Madhav and Parth.

And, of course, last but not the least, I would like to thank all my amazing and loving friends.

PROLOGUE

3 March 2012

It was just another morning. Everything seemed normal. We were all sitting in the living room. Dadoo was sipping tea. Vikram and Mala didi were reading the newspaper hoping that Dadoo too would become interested and pick it up. I was engrossed in reading a memoir I had picked up a couple of weeks ago. Mamma was trying, unsuccessfully, to engage Dadoo in a conversation. Later she left to attend a kirtan in the neighbourhood.

T

he four of us – Daddy, Vikram, Mala didi and I – were sitting in the lawn when Mamma returned after two hours.

Dadoo looked at Mamma blankly and then politely asked, ‘Whom do you want to meet?’

Mamma stared at Dadoo unable to comprehend what he was saying. Before she could respond he repeated, ‘Do you want to meet someone here?’

We were stunned into silence, and looked towards Dadoo. He was still looking at Mamma. Expressionless. Not even confused.

‘What are you saying? I am Asha,’ she said with pain and started whimpering.

‘Asha?’ he muttered as if trying to remember something. Trying to connect. But his face was wooden.

‘I am Asha, your wife.’ Mamma was crying by now.

‘Daddy, don’t you remember Mamma? It’s Mamma,’ said Mala didi.

But Dadoo was blank. He then got up from his chair, looked at Mamma again and then at us. He slowly went inside the house, lay down on the bed and covered his head with a bedsheet …

1

This is an unfinished story. The story of a man dying in slow motion. There are unanswered questions, lots of them. I am at loss to understand what went wrong with him and why.

He chases the mirage of his memory. His world disappears fragment by fragment as he grapples with his ‘reality’. It is not just his being, his self that disintegrates every moment, it is the universe as he knew it that fades into oblivion.

The most painful thing is that he is aware of all this.

He is seeing death; his own death, piece by piece. My heart cries for daddy, my dear Dadoo. Oh! Why?

Is life futile? Why do we suffer this agony, this pain? Is it the fruit of our actions in our previous lives? Accumulated sins? Karma? Human predicament? I have no answer.

It is a sentence whose grammar has gone wrong. There is never a full stop. The thought of a full stop, however, is scary. I shudder.

No, I am wrong. There are full stops. Every moment a part of him disappears. Forever. Names, faces, events – all vanish bit by bit.

On one end is this mesh of myriad threads we call memory and on the other end is his existence. Threads snap. Cut. A face is gone. Cut. A memory sinks in abyss. Cut. Another face, another experience. Gone forever. At times there is a flash. Something lights up. Someone calls. But all attempts to recognize fail. No relationships emerge in the fragmented mind. What is real and unreal has lost the meaning. He oscillates somewhere between being, and not being.

Memory and imagination – these are so important. These are not mere words; these are us. Like everything else, when we have memory we do not value it but when it fades, imagination disappears too and that is the end of our existence.

Dementia and Alzheimer’s are still mysteries. We just have a combination of vitamins, anti-depressants and sleep-inducing pills as a prescription – a more civilized form of chaining and locking up people.

If you have a parent with dementia and you do not want to lock him or her inside the house, the focus of your whole world shifts. More traumatic is the fact that the person you have looked up to, admired, and adored has become powerless and vulnerable. When the roles are reversed and you become the parent, you fall deep into the confusion, bitterness and unwanted responsibility.

An aching pain stings you on and on as you see your parent degenerate. This person had been your bedrock of strength, your father – the person who was always there, who was so knowledgeable and worldly wise. But you see him wither away slowly in front of you, watch his decay helplessly. It makes you angry. But you can’t help.

Not only am I seeing my father – my Dadoo – go through this transition but I have also become aware of my true self – temperamental and escapist. It makes me go berserk.

This is so unjust. But that is what it is – my Dadoo’s world …

2

12 January 2010

The Clinic

We are early; the neurologist is yet to arrive. There are a couple of other people in a reasonably big room waiting for the doctor apart from Dadoo, my husband, Rohit, and I.

Dadoo looks around, ‘Why have we come here?’

‘To see the doctor, you wanted to consult her for your forgetfulness,’ I say, smiling reassuringly.

‘Oh, yes. Is she a doctor for fading memory?’ he asks almost whispering.

‘Yes.’

‘Is this a government hospital?’ he asks.

‘It is a private clinic,’ Rohit replies.

‘Why are we here? We should have gone to the government hospital.’

‘Dadoo, she is the only one in Shimla, there is no other neurologist.’

He is surprised. ‘No one else? No government doctor!’ and then adds, ‘Is she a specialist, I mean, a good one?’

‘Yes, yes, very good,’ Rohit too assures him.

‘Okay,’ he mumbles.

It is such agony waiting in the neurologists’ clinic, not sure of what the doctor would say about your mental stability. The verdict haunts. In the beginning when you still know that something is happening to you, when you are still aware that you are a human being, it is so very dreadful to sit here and wait to know what is wrong with your mind.

I wonder how difficult it will be for Dadoo to tell the doctor that he was losing his brain. He was not just an intelligent educated man but had been professor of math for years. Is he embarrassed? Or nervous? I do not know. But I am sure he is feeling sheepish and wants to run away.

I can see him pretending that everything is fine. But perhaps that is natural. A person waiting in a neurologist’s clinic does not fit into the conventional definition of a patient; he or she looks normal. People with diseases or injuries moan, whine and complain. Dadoo looked so proper in his cream-coloured suit, tie and well-coordinated tan shoes.

He smiles whenever someone walks in. No one is aware how ruptured his brain and soul is. Physical pain is nothing as compared to this.

Our turn. We enter the doctor’s cabin. She gives an affectionate and warm smile, ‘Please sit down.’

‘This is my father-in-law. He’s having a problem with his memory; he’s forgetting things. We’ve got an MRI done and the report says that these are age-related changes but … here’s the report,’ says Rohit.

The doctor takes the report, studies it for a minute or two and then looks at Dadoo smilingly.

‘How are you, sir?’

Dadoo smiles, ‘I am fine. We were just passing by so we thought of meeting you.’

‘That is so nice of you,’ she replies.

Dadoo smiles and says, ‘I have no problem but sometimes I do not remember things.’

The doctor nods.

‘Sir, I will ask you a few more questions? May I?’

‘Questions,’ he laughs and then looks at the doctor amused. This is all a pretension, I can feel that he is under lot of pressure.

She smiles. ‘Yes sir, so here we start. Can you tell me where we are sitting at the moment, I mean the place?’

Dadoo laughs as if this is the most stupid question and then mumbles, ‘What place is this?’

‘Dadoo, you know what place this is,’ I say my heart missing a beat as I look into his worried eyes.

‘Shimla,’ he says. I heave a sigh of relief.

‘Where do you live?’ the doctor asks.

‘Solan.’

‘Very good. What year are we in?’

‘2010.’

‘Which month?’

‘Month … ummm …’

‘Date? What is the date today?’ the doctor asks.

Silence.

‘What is the day today?’

Silence.

‘I mean … Monday, Tuesday or Wednesday?’ asks the doctor patiently.

Dadoo looks blank.

‘How many children do you have?’

‘Four,’ pat comes the reply.

‘Good,’ says the doctor.

‘Spell water backwards?’

He concentrates and slowly spells it out.

‘Okay,

sir, now let us play a small game. I will give you three words to remember and then I will ask you about them after some time. Please do try and remember them. The words are chashma (glasses), kutta (dog) aur gaadi (and vehicle). Will you please repeat?’

‘Chashma, kutta, gaadi,’ Dadoo says quickly. He is back to his amused self now.

‘Yes, sir. That is very good. So tell me how you feel. Is there any other problem that bothers you?’ She then asks him about his sleep patterns, food habits and other minute details. Then after some time she returns to the three words, ‘Sir, could you repeat the three words I requested you to remember?’

‘Yes,’ Dadoo says and then tries hard to jog his memory. ‘One was gaadi, I think, and the other two … I do not remember,’ he mumbles. His hands are trembling now.

‘Please try again. Think,’ the doctor says

He gives a hollow laugh, ‘No, I do not remember.’

I can sense stress in his voice.

‘Okay, not to worry. Let us do some small calculations. Will you tell me how much is 200 minus 7?’

He instantly answers, ‘193’.

And then it goes on.

‘193 minus 7?’

‘186.’

‘186 minus 7.’

‘179.’

‘Very good, now count backwards starting from hundred.’

Dadoo starts, ‘99, 98, 97, 96, 95 …’

‘Good,’ says the doctor.

As I watch him making light of the doctor’s methodology, I see acute stress in his demeanour and a keen desire to get the answers right.

The doctor writes down a prescription and hands it over, ‘He has dementia and it may or may not be Alzheimer’s. We will have to put him on medication and these medicines will have to be changed frequently till we arrive at the right doze and correct combination. Therefore follow-ups are very important. The medicines may make him depressed or hyper-active at times; it varies from individual to individual. All respond differently. You have to keep a watch and give me feedback on any abrupt variation.’

With a heavy heart I ask, ‘Will he improve?’

A World Within

A World Within