- Home

- Minakshi Chaudhry

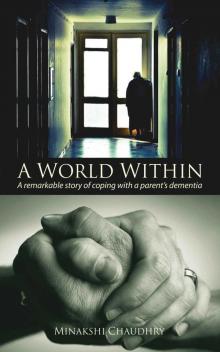

A World Within Page 3

A World Within Read online

Page 3

‘Don’t we have an old photograph?’ Deepak asks.

‘We will find one, in those long lost albums stored in the cupboards, a picture of a young Daddy. That can wait but you tell us about Dadoo now,’ I say to Deepak.

I can feel his anxiety and palpable tension. He wants to talk about Dadoo but he is emotional. Though he is thirty-six he is hesitant to talk in front of us because he is the youngest. Haltingly he starts, ‘The word “impossible” was never in his dictionary for both himself and his children. He gave me full freedom to do whatever I wanted. He never exerted pressure on me; his faith in me was like a rock. I know that no one in the family believed that I would be selected in the National Institute of Technology [NIT], Hamirpur, and that too in the merit list was beyond imagination. I had scored only fifty-four per cent marks in plus two. But Daddy was the only one who said that I could do it.’

I blush as he reminds me of this. I was the one who had gone to check the result and conveyed that he had not made it. I had scanned the list of selected candidates and did not find his name. I did not bother to look for his name in the merit list; I never expected his name to be there! Later, I was quite surprised when I got to know that he was among the top twenty students.

Deepak continues, ‘After engineering when I wanted to do MBA from the Indian Institute of Management [IIM], again all of you doubted me and suggested it was waste of time, for the last nearly ten years not a single student from Himachal Pradesh had been selected in IIM, only geniuses got selected and I was not one of them. But then again only Daddy had faith in me and supported me wholeheartedly. I was called for interview by all the IIMs. It was all because of him. He never forced me to study like my friends’ parents did. He allowed me to proceed the way I wanted to. He was always there whenever we needed a shoulder to cry or someone to talk to. Moreover the confidence that he had in himself was enormous. I am now working in the most competitive global market but I must say that I do not possess that kind of confidence in life that he had. He has so many qualities; none of us have his qualities.’

‘What exactly do you mean?’ I murmur.

‘He always believed that if there is a problem, then there has to be a solution. He never gives up. There is always a sense of security when he is around. Even now I feel if Daddy is here no one can touch us, nothing will go wrong. Mala didi has his compassion and humanity; you have his intellect and worldliness. Vikram has his quality of shouldering responsibility. I unfortunately have none except that I am not a bad person and I am fair in my dealings. But these are so few in all four of us combined. We can’t match what Daddy has,’ he pauses and then continues, ‘I remember one incident that I cherish as a very valuable lesson. I was in class nine and had gone to the market with Daddy. We purchased grocery items from Gupta uncle’s shop. Daddy paid the bill but when we got home and checked the bill, he realized that Gupta-ji had taken seventy rupees less. He told me to go back and return the money. I was reluctant and insisted that it was not our fault and that he miscalculated. Daddy replied, “It is not his fault too, no one would want to take less money. And since we know the truth now, it would be injustice to keep it. Money-related decisions must be based on our inner voice, always listen to your inner voice.” He is my greatest motivator and mentor.’

Vikram says, ‘It is so strange that Daddy is having this problem with his memory, he has not just been a maths teacher, but he has a very analytical mind and he has been so good with money.’

‘Yes, Vikram is right, Daddy supported a big family with his modest salary and he knew how to multiply money. He saved sensibly and invested wisely. He bought land and then sold these plots on premium, thereby growing his wealth. It was his farsightedness that made us what we are today. Each one of us got best education and never felt that he could not support our education however expensive it was. I am in banking sector and I can say with total confidence that he would have done great had he been in banking and finance,’ Deepak adds.

‘I remember another thing,’ Vikram says, ‘he was fearless. I recall that when he bought a car in Nigeria, a red Morris, he drove it straight from showroom to home.’

‘He went alone?’ Deepak is astonished.

‘No, Paul uncle was with him, but it was Daddy who drove. He had never taken a seat behind a four-wheeler earlier. I was amazing. Everyone was surprised and Mamma was so scared. But he said that it was simple, there was not much difference between a two-wheeler and a four wheeler. You just had to apply your mind and concentrate.’

‘I think above all he is a great human being, full of compassion and always willing to help. I remember that once Daddy had gone to Shimla for some work. It was winters. When he came back he knocked at the front door. I looked out of the window and did not recognize him. There was a man in a baniyan [vest], without a shirt. I called Mamma and said that there was a man outside. She said that it must be Daddy. I said that no, he is only wearing a baniyan. “Then no it can’t be your Daddy, he was wearing a coat. Tell the uncle that your Daddy is not in the house, he should come later,” Mamma said. But the man would not leave and kept banging on the door till a scared Mamma opened the door and to her astonishment saw that the man shivering in the vest was Daddy. He told us that he had met a person at Shimla bus stand who was very poor and had no clothes, so he had given his coat and shirt to him,’ Mala did fondly remembers.

Vikram states, ‘Since childhood we have celebrated all festivals in our house. Christmas and Eid are as sacred for us as Diwali and Holi. This is because of him. It is so painful to see him lose his memory.’

And then Mala didi says something that makes me think ‘Rewa, you are a writer. Why don’t you share the story of Daddy with everyone else?’

I nod and wonder how dementia and Alzheimer’s is destroying his healthy mind.

5

What is dementia and Alzheimer’s?

Dementia means ‘without mind’ and the word comes from Latin language. The Oxford Dictionary defines dementia as ‘a serious mental disorder caused by brain disease or injury, that affects the ability to think, remember and behave normally’.

Named after Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and neuropathologist, Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia. The prognosis of the disease is progressive irreversible memory loss, disorientation and delusions. Initially the patients lose the ability to do routine things like buying groceries, withdrawing money from the bank and paying bills. Gradually, they lose sense of place and time, forget people around them and even fail to recognize themselves. In the end they forget not only to eat and swallow but also to breathe.

It is a dreadful disease that eats you alive. Although it is more common in the elderly, it can also occur before the age of sixty-five. It has no cure and even after advancements like MRIs and CT scans, final diagnosis that the disease is Alzheimer’s can be made only after the death of a person, by opening his skull.

According to the Alzheimer’s Association:

‘Dementia is a general term for a decline in mental ability severe enough to interfere with daily life. Memory loss is an example. … Many people have memory loss issues – this does not mean they have Alzheimer’s or another dementia. … While symptoms of dementia can vary greatly, at least two of the following core mental functions must be significantly impaired to be considered dementia: memory; communication and language; ability to focus and pay attention; reasoning and judgment; [and] visual perception. … Dementia is caused by damage to brain cells. This damage interferes with the ability of brain cells to communicate with each other. When brain cells cannot communicate normally, thinking, behavior and feelings can be affected. The brain has many distinct regions, each of which is responsible for different functions (for example, memory, judgment and movement). When cells in a particular region are damaged, that region cannot carry out its functions normally. … There is no one test to determine if someone has dementia. Doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s and other types of dementia based on a careful medical h

istory, a physical examination, laboratory tests, and the characteristic changes in thinking, day-to-day function and behavior associated with each type.’*

‘Alzheimer’s is a progressive disease, where dementia symptoms gradually worsen over a number of years. In its early stages, memory loss is mild, but with late-stage Alzheimer’s, individuals lose the ability to carry on a conversation and respond to their environment. … As Alzheimer’s advances through the brain it leads to increasingly severe symptoms, including disorientation, mood and behavior changes; deepening confusion about events, time and place; unfounded suspicions about family, friends and professional caregivers; more serious memory loss and behavior changes; and difficulty speaking, swallowing and walking.’*

And my Dadoo is not the only one. The World Health Organization estimates: ‘The total number of people with dementia worldwide in 2010 is estimated at 35.6 million and is projected to nearly double every 20 years, to 65.7 million in 2030 and 115.4 million in 2050. The total number of new cases of dementia each year worldwide is nearly 7.7 million, implying one new case every four seconds.’**

About five years back Mamma had started complaining that it was becoming difficult for her to handle Dadoo whenever they went to stay with Vikram or Deepak during winter months. He was always restless – and we thought it was because he got bored and was not comfortable in the new environment – he wanted to rush back to Solan.

Exasperated we would tell him that when in Solan he would always long to be with his children; so why was he unhappy staying with them for a couple of months? I had no idea then that stability of his daily routine and the familiarity of the place was the best way to keep him secure and comfortable.

*http://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_what_is_alzheimers.asp

**http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/priority_medicines/BP6_11Alzheimer.pdf

Oh how many times have I heard – it is very difficult for the children to take care of old parents. It is even more difficult to handle a parent suffering from dementia. Not only do you need time and finances but you also require many supportive and sensitive family members around. You may love your parent but this disease can slowly make that love evaporate. It is extremely traumatic and difficult to manage a person suffering from dementia, especially in the small families that we have now.

6

10 April 2010

I am excited. My Dadoo is coming today. I wait impatiently, looking down for their vehicle, Vikram’s Honda City.

I restlessly pace to pass the time in the small open space outside our cottage in Shimla. As I see the car, I literally run down the fifty odd stairs. Dadoo is in his traditional Kullu topi, and patti ka coat which I had bought for him from Rampur Bushahr. He is looking dazed. I glance cursorily at Mamma, she smiles. Excitedly I move forward calling out, ‘The best person in the world has come, my Dadoo has come.’ He beams and looks at me with love and pride. I hug and kiss him by dozens. I have never ever felt odd kissing him – on roads, in parties and in front of anyone – and I don’t bother about what people think.

As he settles outside the cottage in the sun he says, ‘Enjoy every moment, there is nothing in life.’ I nod. Now every one of his phrases is very precious to me, they have deeper meaning.

Lakshmi, our housekeeper, gives him tea; he sips it and says, ‘This tea is very tasty.’ And then adds, ‘How much money do you give her every month?’ I mumble and then guiltily lie, ‘One thousand rupees.’

‘One thousand,’ he says and then asks Mamma, ‘How much do we give to the lady in Solan?’

Mamma doesn’t know what to say, I intervene, ‘Five hundred.’

‘But the lady there comes for two hours and she does not cook,’ he says unhappily. I nod. Ramesh, the other person who takes care of my house, brings hot gulab jamuns: Like everyone in the family Dadoo too has a sweet tooth.

He bites into the piping hot gulab jamuns with pleasure. He is awed when I tell him that they are made at home.

‘Who made them?’ he asks surprised.

‘Ramesh.’

‘How much do you pay him?’

‘Nothing,’ I say, the guilt of lying increasing twofold. He frowns.

‘Then how does he stay here?’

‘He is in a job. I give him a place to stay and food to eat.’

‘Oh.’

Recently all of us have started lying to him about price of things. We undervalue so that he remains calm. Otherwise he gets agitated for ‘wasting’ so much money ‘unnecessarily’.

Mamma was not comfortable in coming frequently to my house, because regular and long visits to a married daughter’s house are generally considered inappropriate, though Dadoo had no qualms about it. But now she realizes that she gets ample rest here unlike Solan where she has to take care of Dadoo alone with no help.

And then Dadoo says, ‘I love Rohit a lot.’

I nod.

‘He is unique, I have never seen anyone like him.’

‘He also loves you a lot, Dadoo,’ I say, ‘in fact he is more worried about you than I am. He is the one who always says that you should come and stay with us.’

Dadoo asks innocently, ‘Can I stay here with you forever?’

‘Yes, forever,’ I mumble.

I am both saddened and happy by this statement. I remember Mamma’s call one morning when she informed me how Dadoo was crying inconsolably while later telling her that she didn’t have to worry because Rewa and Rohit were there to look after her. Mamma too was sobbing while telling this to me. I felt an ache in my heart: He has two lovely sons yet he feels more attached to us.

‘Give her the gift that we have brought,’ Dadoo said interrupting my reverie.

‘Gift? I haven’t brought any gift,’ says Mamma.

‘What! Give her the gift.’

‘Kuch nahin layee [I have brought nothing], I have brought no gift,’ Mamma asserts.

‘Don’t lie. Go inside and bring it from the bag.’

I don’t want them to argue and try to console him, ‘It is okay, Dadoo.’

‘No,’ he says, he is shouting now, ‘go inside and give her the money otherwise I will go and get the purse.’

I feel uneasy. I don’t want any money. But I don’t know what to say to him. He is so agitated; a few minutes back it all seemed so normal.

Mamma says, ‘I will give it to her, why are you getting angry, Rohit will feel bad.’

‘Give it to her in front of me,’ he repeats becoming angrier.

I budge in, ‘Okay, okay. I will bring the purse,’ I go inside, Lakshmi is mopping the floor. I don’t want to leave footprints on the wet floor, so as I turn I bump into Dadoo. He has followed me.

‘Let Lakshmi mop the floor and let it dry, then we will get the purse.’ I say hugging him.

‘Okay’ he says, he is back to normal.

‘How many days will I stay here?’ he asks me.

‘Ten days, Dadoo.’

‘Will Rohit have the time? I have to discuss many things with him.’

‘Yes, after office hours he will have lot of time,’ I say kissing his forehead.

‘I have so much property,’ he murmurs. I nod.

‘There is one piece of prime land here in Shimla too,’ he says.

‘No, Dadoo.’

‘Of course,’ he says affirmatively. ‘I will ask Rohit,’ he adds dismissing me.

‘Okay, do that,’ I give him a glass of juice.

‘Is this fresh?’ he asks.

I shake my head.

‘Then?’

‘It is from a tetra-pack.’

‘You put water in it?’

‘No, it is pure juice.’

‘How much did it cost?’

‘Sixty rupees.’

‘Sixty rupees?’ surprised he asks, ‘how many glasses, four?’

‘Yes, about four.’

‘Where do you get it?’

‘In a shop here.’

‘I want to buy too.’

I nod.

‘No, Dadoo. It is going to be forty-two thousand rupees and that is when you will turn eighty.’

‘No, it will be fifty thousand rupees after fifty years of service.’

I am zapped. I want to say that you have retired twenty years ago and had served only thirty-seven years. ‘It will increase in May when you turn eighty,’ I say patiently.

‘I think I have a lot of money, even this pension is enough.’

I nod.

‘Will we go to the market?’ he asks suddenly.

‘After lunch, Dadoo,’ I say.

‘Do I know someone here?’

‘Yes, you have a friend here, Malkiet uncle.’

‘What is he? A doctor?’

‘No, Dadoo, he is a lawyer.’

‘Yes, yes, vakil hai.’

‘Is Rohit going to be promoted?’

‘Yes, towards the end of next year.’

‘What will he become?’

‘Deputy Commissioner.’

‘Wah, wah, he will be DC,’ he says beaming with pride.

‘May be next to next year,’ I say clarifying, happy that Rohit is nowhere in the near listening to this fancy prediction.

‘I am so thankful to God. You two have done me proud. All my children have done me proud,’ he adds.

‘How much does Rohit earn?’

‘Eighty thousand rupees.’

‘Do you save?’

‘More than forty thousand rupees, Dadoo,’ I mumble, winking at Mamma.

‘Is this house on rent?’

‘No, government accommodation.’

‘Vikram also earns ninety thousand rupees and so does Deepu,’ he says looking at me for confirmation.

I nod.

‘Does Deepu earn ninety thousand rupees?’

‘Yes,’ wondering what his reaction will be if I tell him that Deepu earns more than five lakh rupees a month.

A World Within

A World Within